The Impact Of Inaction – Why Aren’t We Listened To?

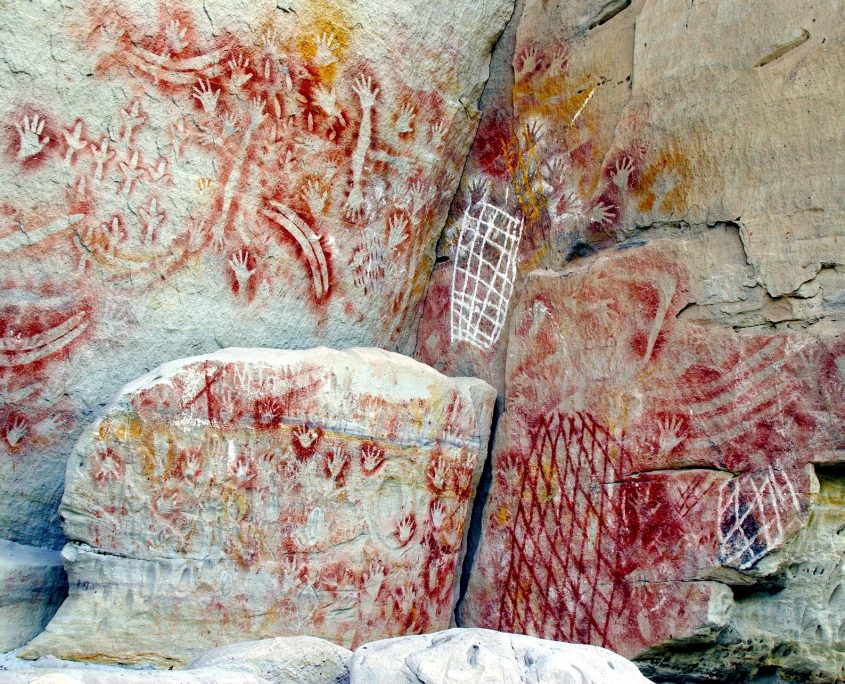

In the 200+ years since the ‘white settlement’ of Australia, various government has accomplished a fair bit. They’ve built a country from the ground up, conquering what they perceived as a harsh land and providing the citizens with the luxuries of Western civilisation. To achieve this, they’ve attempted to decimated an entire thread of humanity, wiping out tribes and language groups in the never-ending march of progress. They’re removed children from their mothers, abused power and left Aboriginal people, the First Australians, so much the worse for their coming.

Now, the government likes to think they can make amends, by apologising for the past and consigning it to the filing cabinet of history. They’ve muttered their apologies, as though a single sorry might act as a panacea, a Band-Aid on the pulsing artery of Aboriginal trauma. Unfortunately, the two hundred years of government policy have left a terrible legacy. PM Rudd acknowledged that the 50 years of policy preceding his 2008 Apology statement had been a failure. He promised a new beginning. What Aboriginal people got instead was an intensification of the intervention, rebadged as ‘Closing The Gap’. Rather than that new beginning, Aboriginal people have come to realise not only is it ‘business as usual’, but the pressure on them to assimilate is greater than ever.

Quality And Quantity

Let us give you an example of one of the many places governments have failed to properly engage with Aboriginal people towards their aim of improving them. In the march towards closing the gap, past and present Governments have been data focused. Unfortunately for Aboriginal people and service providers, their point of focus has been overwhelmingly the longevity, or life expectancy, of Aboriginal people. Don’t get us wrong, we feel that it is shocking that Aboriginal Australians do not live as long as their non-Aboriginal counterparts. However, we have to wonder whether, instead of quantity, we should be focusing on quality of life.

Improving the quality of life for Aboriginal people is almost guaranteed to have the knock-n effect of increasing its quantity. The key thing to remember when we’re thinking about quality though is the cultural space through which is it measured. The simple fact is that quality of life must be considered from an Aboriginal cultural space, even if that means something different to policymakers. Quality of life is, after all, a lived experience, and not something that can just be transplanted onto an Aboriginal setting.

Inaction In Action

To those looking in at our governmen, it’s quite clear what is going on. They are quite frankly paralysed by their own misunderstandings, and their inability to enact positive change through meaningful and engaged approaches. What we are seeing now is inaction in action. That is, a government operating in a risk-adverse environment where policymakers and advisors are unable to do anything that doesn’t fit into their comfort zone. As a result, everything they put forward is entirely cemented into their own cultural framework, and is unlikely to allow Aboriginal Australians operating within different cultural parameters a chance to be positively impacted by that policy.

In fact, even when Aboriginal people do talk to the government about what they want to do and what they hope to achieve, through community engagement, they are often ignored. Usually this comes down to an inability within the government to make an Aboriginal perspective on life fit into our current system. They are culturally strangled by their own rules, and what they believe to be appropriate. As they say, you can only know what you know.

That means that if you’re working in a different cultural mindset, and you aren’t making the switch when dealing with other cultures, you’re only going to get poor results. This is why our governments have wasted excessive funds, and caused serious damage, to people trying to achieve a quality of life that it outside of the parameters of a white Australian cultural setting. This isn’t just about health either. We’re seeing the same story in housing and education as well, all because community engagement is being done as a side-thought, a box to be ticked instead of an opportunity to get the voice of the community into its own future.

So, What Next?

We believe that the way forward will come from engaging in a more meaningful way with Aboriginal people in their first language, to get a true understanding of what communities want and need to succeed. This means that most of the community engagement undertaken needs to be done by Aboriginal people themselves. Yes, we do need to be prepared that this won’t be a smooth process with a guaranteed win every time. The history of government interaction with Aboriginal Australians is littered with failed projects and funding black holes, and we have little to show for it. Now it’s time to pass the torch of ‘improvement’ where it belongs: in the hands of Aboriginal people.

We feel that the only positive solutions for Aboriginal people will be for them to approach their own problems from within their own cultural framework. Not only must they be heard, but they have to be able to articulate and proceed in to an action that they feel will result in positive outcomes for their community. Only through this kind of community engagement are results even on the horizon, but the process will be a long one. After all, successive governments have progressively worsened the state of Aboriginal people, under the guise of improving them. Perhaps now we should allow the people to improve themselves, as only they can know how.