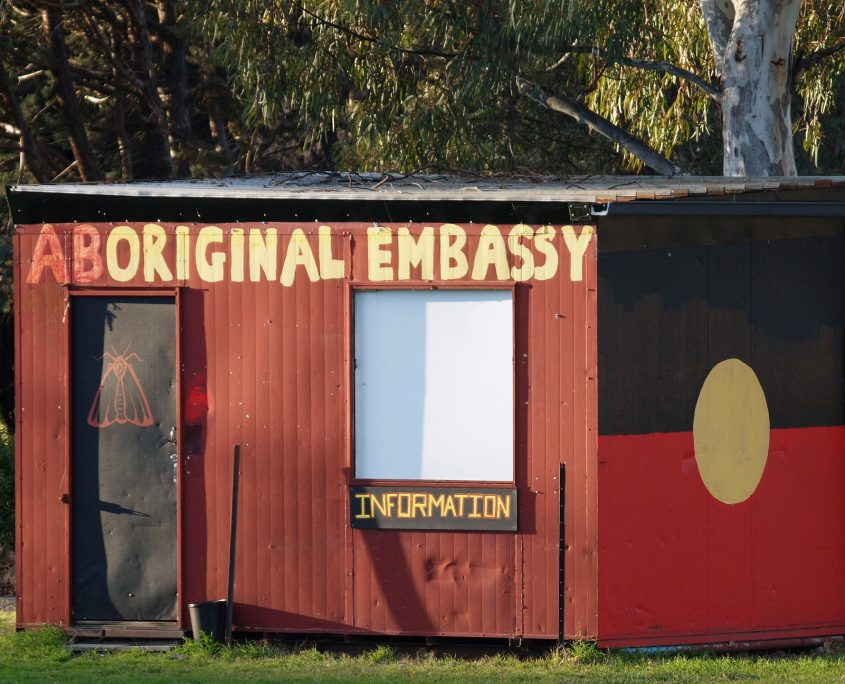

Any time the subject of foster care and government child protection policies is raised with Indigenous people in mind, it creates ripples in the wider community of experts, carers, and people themselves. There has been a proven history of long-term failures in this country when it comes to proving Aboriginal children with Out-Of-Home Care, and although the government would like to continue as if saying sorry were enough to heal the traumas of the past, it isn’t. While the harmful and traumatic child removal policies of the Stolen Generations are now over, current policies meant to serve the betterment of the next generation of Aboriginal Australians continue to fail, and we need to do something about it.

What We Aren’t Arguing With

The right of every child to be raised in a loving, safe environment is not disputed. All the evidence, over decades of varied studies, have indicated that children who are subject to trauma or stress in four significant areas of development – physical, emotional, intellectual and social – are unlikely to grow into well-balanced adults. What also needs to be considered, particularly when dealing with children from Traditional Aboriginal backgrounds, is the spiritual aspect of development. Here we aren’t talking about religion so much as tradition, an important part of life for Aboriginal people.

Also not disputed, is the fact that there are growing instances of individuals and communities across Australia being subjected to varying degrees of stress in all five areas, regardless of race and background.

Of course, Aboriginal Australians are no exception.

There is no doubt that many Aboriginal Australian children are subject to conditions throughout childhood that no child should experience. Unfortunately, the mainstream response to this is potentially causing an even greater level of stress.

The current primary aim of our child protection system is to “protect the children”. It is a maxim that makes sense right up until the point it is enacted. See, there’s more to protection that what’s on the surface. Our dedication to keeping children safe is doing more harm than we can imagine, because making sure children are physically safe is not enough. There are other areas of the child development equation that are being entirely forgotten, but at the moment child removal is about the only move the government seems to have in its repertoire.

The Facts As They Are

There are currently over 15,000 Indigenous children in Out-Of-Home Care in Australia [1], a number that has risen 65% since 2008 [2]. In fact, despite making up just 5.5% of the population of children aged under 17, Indigenous kids represent 35% of the number of kids in the foster system2. Kids aged 1-4 who are Indigenous are 11 times more likely to be living in out-of-home care than a child not of Indigenous background [3].

Some suggest that the numbers of children being removed from their families is greater than at any other time in our recent history. As records were either destroyed or poorly kept in the decades leading up to the 1990s, this is hard to confirm, but certainly numbers have risen dramatically since the early 1990s [4]. Significant attention was drawn to this issue in the 1997 Bringing Them Home report [5], which showed that Aboriginal kids are dramatically over-represented in both child protection and Out-Of-Home Care, thanks largely to decades of forced removal and assimilation policies. The intergenerational effects of those removals, combined with cross-cultural differences in child rearing, are having a devastating effect on contemporary Aboriginal lives. Other studies have noted that family violence, substance abuse, overcrowding and inadequate housing also play a part [6].

Fixing The Current System

The current foster system in Australia, based on recommendations from the Bringing Them Home report, places Indigenous children removed from their homes first with extended family, then within their community, then to other Indigenous people, before placing them with a non-Indigenous family. This system seems, on the surface, to work well, but the children emerging from it are still suffering from the same dysfunctions of previous generations, and we need to ask why.

The fact is that the families these children are coming from, as well as many of the families they are placed with, are still suffering from high degrees of familial stress. Indeed, removing children from one traumatic environment and placing them into another similarly stressful home setting is just as traumatic. Unfortunately, placing Aboriginal children with non-Aboriginal carers can be equally traumatic for these children, and cause them to lose touch with their Aboriginal identity.

We would suggest that where Aboriginal children are placed in non-Aboriginal family settings, those children should be connected with Aboriginal organisations and networks, so that individuals in these networks can become something akin to mentors for these children and the foster carers. In this way, children outside of their home cultures can be connected to their original identity and have a strong foundation from which to grow. Unfortunately, our government doesn’t see the benefit of this because it’s goes beyond physically and emotional caring, into something that governments don’t understand, and can’t quantify.

At the end of the day, all children from all backgrounds have the right to be cared for in an environment that is safe and secure. That might not look the same for everyone, and our system needs to account for that. We also need to understand that if the current issues with the Australian foster care system aren’t addressed history will be repeating itself. Instead of having a Stolen Generation, we will be creating a Lost Generation, with the same trauma and identity issues that many Aboriginal Australians struggle with today.

[1] Child protection services, 2016 Report on Government Services, www.pc.gov.au

[2] Children in Care, Australian Institute of Family Affairs, www.aifs.gov.au

[3]Child Protection Australia, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. www.aihw.gov.au

[4]Bringing Them Home, Chapter 21, Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission Report. www.humanrights.gov.au

[6] Child protection and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. Australian Institute of Family Services. www.aifs.gov.au