The 12th Annual Closing the Gap Report: A Need for More Effective Community Engagement?

Since Kevin Rudd’s 2008 National Apology to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and the subsequent commencement of the Closing the Gap initiative, there have been 12 annual reports tracking Australia’s national progress toward closing health, education, and employment gaps for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. Closing the Gap, since its inception, has set 7 targets with varying deadlines: Halve the child mortality gap by 2018; enrol 95 percent of all indigenous four-year-olds in early education by 2025; close the gap in school attendance by 2018; halve the gap in literacy and numeracy skills by 2018; halve the gap for year 12 attainment or equivalent for those Indigenous Australian aged 20-24 Years; halve the gap in employment outcomes by 2018 and; close the life expectancy gap within a generation by 2031. While this most recent report highlighted that some progress has been made towards these targets, only 2 out of the 7 are on track to be achieved within their respective deadlines, being early childhood enrolments and year 12 attainment. Over half of these have already fundamentally failed, with deadlines ending 2 years ago. This begs the question: where is the government failing in its efforts to close the gap and what strategies can be undertaken to rectify these failings?

Our Perspective

From our perspective here at Cross Cultural Consultants the answer to that question lies in truly effective community engagement, leading to policy that is genuinely co-designed with communities for place-based solutions that have real community buy-in. Australia is a vast continent, and although there is a trend in the issues facing many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, there is a tendency to see all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people as one single homogenous group. This could not be further from the truth. There are in excess of 50 language groups in the Northern Territory alone, and complex layers of historical events and traumas that differ from group to group. Considering these complexities, it is no wonder why policy addressing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander issues that have a ‘one size fits all’ approach fails to deliver desirable outcomes.

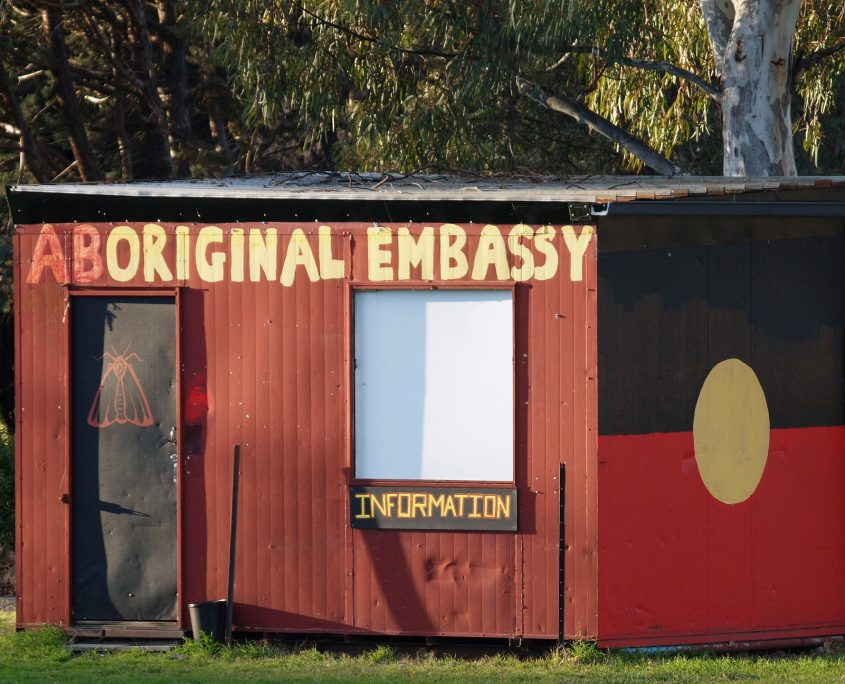

In 2018 the Coalition government and the Coalition of Australian Governments (COAG) committed to, and begun undertaking steps toward, a Closing the Gap refresh that revises targets and priorities, promising to work together with Indigenous people to set a new agenda (NIAA, 2019). In response to this year’s report, both the Prime Minister Scott Morrison and the Leader of the Opposition Anthony Albanese displayed a rare vein of bipartisanship, agreeing that the current approach to Closing the Gap is not working. The Prime Minister himself admitted that a “top-down, government-knows-best approach,” which does not work in partnership with Indigenous people is the wrong model to follow and that the overhaul of the framework as per the 2018 commitments would be led by Indigenous Australians (Higgins, 2020). The truth of this Indigenous led overhaul remains to be seen, however the concepts underlying the alleged revised approach can be considered as a step in the right direction.

Unfortunately, as is the case with so much policy, what the head says is not necessarily what the hands deliver. Promises made in federal and state parliaments are filtered through various departments and public servants, converted into requests for quotes and tenders that all too often sacrifice quality for the sake of time and money. CCC has worked on countless tenders and undertaken jobs where community and stakeholder engagement, although included within the scope of works, has been woefully under-resourced in terms of its scope and allotted time for completion. Effective community engagement, in a landscape as complex and varied as Australia’s, is time consuming. However, laying the groundwork for tailored policies through quality community engagement and generating genuine community buy in, while slow work at first, is more likely to lead to a faster and more efficient implementation. Moreover, tailored solutions led by communities are more likely to legitimately contribute to building social capital and capacity, thereby improving outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people across the board, including in the areas targeted by Closing the Gap. Such an approach focuses on community empowerment and reflects the notion of giving people a hand up, rather than simply a handout.

Closing the Gap for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people is not a simple process, as the last 12 years have demonstrated, and it will not be achieved overnight. However, effective community engagement in policy making, which leads to community buy in and empowerment, is in CCC’s opinion the only way to truly achieve better outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, and for Australia as a whole. Put simply in the Uluru Statement, “When we have power over our destiny our children will flourish… they will walk in two worlds and their culture will be a gift to their country” (Uluru Statement, 2017).

References:

Higgins, I. (2020, February 13). Closing the Gap report shows only two targets on track as PM pushes for Indigenous-led refresh, ABC News. Retrieved from https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-02-12/closing-the-gap-report-2019-indigenous-outcomes-not-on-track/11949712

National Indigenous Australians Agency, Australian Government. (2019). About Closing the Gap. Retrieved from https://closingthegap.niaa.gov.au/about-closing-gap

The Uluru Statement. (2017). The Uluru Statement from the Heart. Retrieved from https://ulurustatement.org/the-statement