PTSD And Its Impacts In Aboriginal Australia

We often associate PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, with soldiers returning from combat, but in fact it can develop and be experienced by anybody who has been through a traumatic event. It’s just now that the general public is starting to realise that PTSD isn’t just a ‘war condition’, but a life condition. Over the years those living with PTSD have struggled for recognition, helped partly by the fact that they knew what they faced, and how they may begin to combat it. Imagine then, an entire group of people suffering PTSD across generations who do not have a good understanding of their condition, and who are unsure of how to tackle it.

Such is the reality of Aboriginal Australia.

A survey from 2008 indicated that almost one-in-three Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults have “experienced high levels of psychological distress” [1]. This is more than twice the rate that was reported for non-Indigenous Australians at the same time.

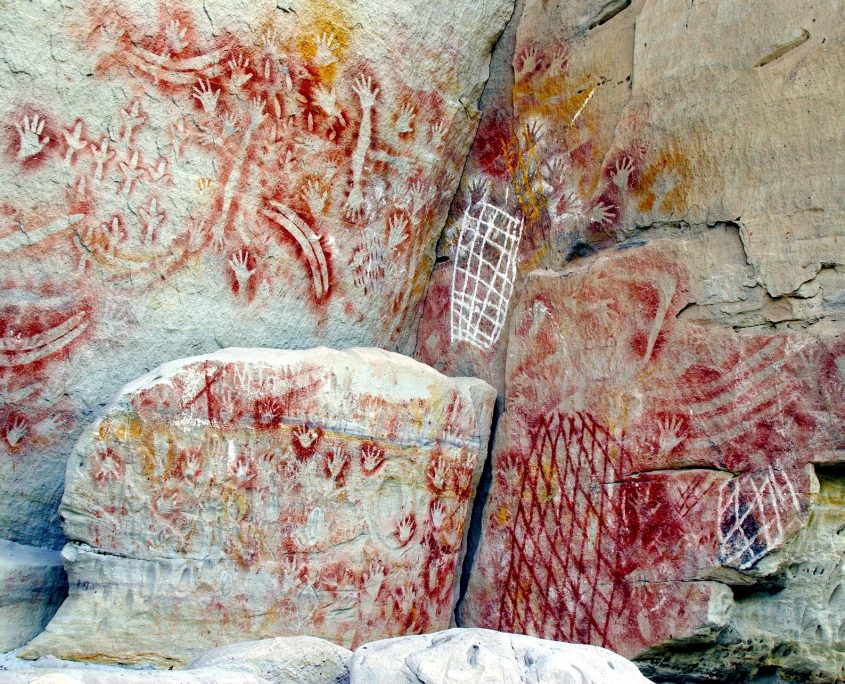

In more than two centuries Indigenous Australians have suffered at the hands of colonists, missionaries and politicians, all sure they were doing ‘the right thing’. They have been subjected to “unprecedented levels of political, social, economic, environmental and physical violence” [2].

As Paul Keating said in the Redfern Address:

“It was we who did the dispossessing.

We took the traditional lands and smashed the traditional way of life.

We brought the diseases. The alcohol.

We committed the murders.

We took the children from their mothers.

We practised discrimination and exclusion.

It was our ignorance and our prejudice.

And our failure to imagine these things being done to us.” [3]

Massacres, exclusion, colonial law and white privilege have left Aboriginal people broken, and dealing with the effects of PTSD not just as individuals, but in an intergenerational way. We’re talking about more than the psychological trauma of an individual, which is a challenge of itself, but the trauma that runs across generations, referred to by Atkinson as trauma lines:

“These trauma lines show the increase of so-called mental illness, alcohol and drug misuse, sexual and physical abuses and suicide attempts that reflect the pain of people’s lived experiences today.” [4]

Now we have two options in looking forward to a future Australia, where equality is a foundational right, not just a political catchword. Either go the way policymakers currently lean, seeing Aboriginal people as a failed group, or we see deeper than that, and recognise the long-term effects that PTSD can have on physical and mental health and wellbeing.

Currently, Australian politicians and those charged with protecting Aboriginal welfare have failed to apply what we know about PTSD to Aboriginal Australia. Our denial is hubris, but it’s not us that we’re failing: it’s Aboriginal people. This denial is one of the primary reasons that many programs specifically targeting First Australians aren’t getting results. It’s why schooling programs, mental health programs, wellbeing programs, and many other ‘closing the gap’ initiatives are doomed from the get-go. Essentially, it’s the real life version of forcing square pegs in round holes.

It’s Only Getting Worse

Unfortunately for Aboriginal people, intergenerational PTSD isn’t something that goes away with time. In fact, with each generation of people the issues faced are worse and worse, the trauma lines run deeper, and it’s hard to see a way forward. As older generations work to fight their demons, they are often caught up in substance abuse [5], leading to newer generations suffering with conditions like foetal alcohol which further adds to the trauma. We’re in a cycle that has to be broken, and now is the time.

What Can Be Done

The intergenerational trauma suffered by Aboriginal people isn’t something that white Australia can fix, and that’s probably the biggest hurdle for us to accept. Like so many other times in the past, we feel that we were the answer, but the truth is that the answer has lain with Aboriginal people from the beginning.

It is only Aboriginal people who can heal the wounds of the past, because we simply can’t understand the trauma that has been suffered by them, individually and as a group, for the last two centuries. We cannot understand the blatant murder and massacre of their ancestors, the denial of their cultural identity, the removal of their children, the separation of families, and the crushing of their spirit. It is a trauma that white Australia wants to wipe from the history books, because we are that guilty. But as Keating said, “guilt is not a very constructive emotion”, only opening our hearts and embracing practical solutions will net the future we hope to have for our great nation.

It’s time to stand up and accept that white Australia has done a number on Aboriginal Australia, but it’s not too late. It will take years for us to overcome the past, but that doesn’t mean we aren’t able to reach for the future.